BioEYES Awarded Viktor Hamburger Outstanding Educator Prize

By Marsha E. Lucas

The Society for

Developmental Biology awarded the 2012

Viktor

Hamburger Outstanding Educator Prize to

BioEYES and

its co-directors

Steven Farber of the Carnegie

Institution for Science and

Jamie Shuda of the

University of Pennsylvania. BioEYES is a K-12

science education program that brings live zebrafish

into the classroom to teach basic biology, including

development, genetics, and ecology. The week-long

program has students identify male and female fish,

set up crosses, collect embryos, make scientific

observations and test hypotheses.

|

|

|

Steven Farber (Image courtesy of NY

Times) |

Farber, a

developmental biologist, and Shuda, a former 3rd

grade teacher, formed BioEYES in 2002. It was a

natural outgrowth of the lab tours Farber began

giving in 2001 as an assistant professor at Thomas

Jefferson University during their campus-wide “Take

Your Child to Work Day.” The children were able to

observe adult zebrafish, as well as developing

embryos and larvae under the microscope. They

overwhelmingly reported back that seeing the fish

was the best part of their day. After countless lab

tours and slightly annoyed lab personnel, Farber

asked the Dean if they could get money to hire a

full-time person to do outreach. Shuda came on board

soon after.

The partnership of a

scientist and an educator made BioEYES a success.

Shuda was able to take Farber’s many great ideas,

and then hone in on those that were actually doable

for a classroom of 30 students. She studied the

educational standards for different age groups and

designed the BioEYES program around them. In an

interview prior to the SDB meeting she said her

focus was “how can we take something that’s already

suppose to be taught, but do it in a way that’s very

student centered, that actually gets them to explore

science, and allows the teachers to actually have

fun teaching these concepts.” The program gets

students to think like a scientist while at the same

time reinforces basic reading, writing, and math

skills.

|

|

|

Jamie Shuda with two BioEYES students.

(Image courtesy of University of

Pennsylvania) |

“We teach in some of

the most elite private schools in Philadelphia and

some of the poorest neighborhoods in West

Philadelphia and everybody gets a learning

experience that they carry with them,” Shuda said.

“I think that that’s what teachers appreciate ...

that you don’t have to read on grade level to do

BioEYES. English doesn’t have to be your first

language.” BioEYES is for everyone.

In fact, student

assessments across age groups show the students do

learn the concepts put forth in their BioEYES

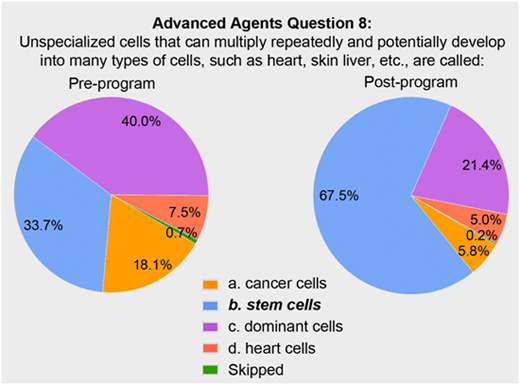

modules. The pie graph below, for example, shows results

of an advanced assessment question geared

toward high school students. After a week of

BioEYES, more students

know what a stem cell is.

|

|

|

2010-2011

BioEYES Advanced Level Assessment

Question Results for Baltimore.

(Image courtesy of BioEYES) |

Both Farber and

Shuda expressed their appreciation for BioEYES being

recognized by the developmental biology community.

“I feel just ecstatic about,” Farber said. “I always

tell people I didn’t wake up one day and think that

BioEYES in all of its forms and success was the

plan. I was just starting kind of small and I think

once Jamie got involved and really took off with the

idea, it just took on a life of its on. So, it’s

gratifying ... and I think the SDB as a partner has

really helped us at critical times in keeping it

going and supporting its growth.”

“For me as an

educator, I think it's fantastic that there’s a

science society ... that is so interested and

passionate about education,” Shuda said.

More than 50,000

students have participated in BioEYES in

Philadelphia, PA; Baltimore, MD; South Bend, IN; and

Melbourne, Australia. According to Shuda, there is

currently a waitlist in most of these cities of

teachers who want to do BioEYES. Shuda said, their

priority going forward is “growing the program to

meet the demand.”

This of course

requires adequate funding. Farber and Shuda are

always writing grants. “We are constantly

strategizing and we have panic moments,” Farber

said. BioEYES is funded by many local foundations

who want to support science education. They also get

funding from faculty who want to add an outreach

component and enhance the “broader impacts” of their

grants from the National Science Foundation or the

National Institutes of Health. BioEYES is written

into their grant proposals and when those grants get

funded, BioEYES gets money to continue their

programs. In addition, the grant recipients and

their lab members can take part in an already

existing program.

In order to meet its

growing demands the program also seeks to develop

more master teachers. These are teachers who have

had BioEYES in their classrooms for at least two

years, have attended the teacher training sessions,

and are comfortable with the material. “We call on

them to come back and train new teachers and help us

recruit new teachers,” Shuda said. “When they sign

up for their BioEYES week, we actually just give

them all the equipment and supplies, and they

conduct the experiment with their students on their

own.”

These master

teachers often report back on changes they have made

or activities they created that they think could

benefit all of BioEYES. “That has helped us expand

... and grow in a way we hadn’t anticipated,” Shuda

said.

|

|

|

Scott Gilbert presents Farber with the

Hamburger Prize at the 71st SDB Annual

Meeting in Montreal, Canada. Shuda

was unable to attend and received her

award following the meeting. |

Farber actually

expected teachers to pick it up faster. “I thought

it would be easy and that every teacher would become

a master teacher because I guess I didn’t really

understand the literacy levels or the variation in

science literacy among teachers,” he said.

This is why Shuda

and Farber are looking to expand the teacher

professional development aspect of BioEYES. “When

you really change substantively a teacher, you

change all the kids that teacher’s going to teach

[throughout] their career,” Farber said.

They also want to

affect pre-service teachers—those in the process of

getting their degrees. “How do we change their

experience as they’re learning about education in

science when they actually can afford the time to

spend in labs?” Shuda said. “If we take it seriously

and actually integrate it into their academic

experience, then we’re preparing them I think even

more.”

To help facilitate

this, BioEYES is working on a partnership with the

Johns Hopkins School of Education, where Farber and

Shuda have both been given secondary appointments.

The School of Education has “acknowledged the impact

of our program and [sees] it as a model for

replication, and that will bring our voice to the

table so we can talk about what we think the future

of both professional development and pre-service

should be for teachers,” Shuda said.

The program has come

a long way since its early days. Shuda said, “I’m

just extremely grateful that a society, the Society

for Developmental Biology, has acknowledged our

program and has supported us from the ground up. ...

Being able to say that SDB has been the support for

us as we’ve grown has just been a really great

experience for Steve and I.”

|